On my mind today is the stranger who visited my finch feeder Saturday. This morning, I topped the feeders and put out a new suet cake with the hope that this bird I’ve never seen before might return.

I suspect, though, he/she may just have been passing through, quite possibly en route to or from a Great Lakes Basin island.

I suspect, though, he/she may just have been passing through, quite possibly en route to or from a Great Lakes Basin island.

Larger than a sparrow, smaller than a jay—maybe the size of a starling? White breast with a black band around the neck (at least on the breast; thinner than the top band on a killdeer). Maybe the wings looked like sparrow wings in terms of colors/pattern? The crown of the head had a gray stripe. On each side of the gray was a stripe or patch of rusty brown (going toward the orangey color of a bluebird’s breast).

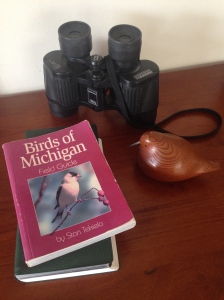

This rusty color is what caught my eye, even though I was wearing my computer glasses. I immediately recognized the bird as one I didn’t know. I whipped my glasses off and swung the binoculars, kept on my desk for such occasions, up to my eyes. And then tried to memorize.

Before I could reach for my bird guides, the bird was gone. Despite pouring over my “go-to” bird books: Birds of Michigan Field Guide—112 species organized by color; I looked at orange, brown, white and for the black neck band—and The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds: Eastern Region (considering perching and tree-clinging birds), I have yet to identify my visitor. Any ideas?

Before I could reach for my bird guides, the bird was gone. Despite pouring over my “go-to” bird books: Birds of Michigan Field Guide—112 species organized by color; I looked at orange, brown, white and for the black neck band—and The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds: Eastern Region (considering perching and tree-clinging birds), I have yet to identify my visitor. Any ideas?

This puzzle is a good reminder to 1) get out hummingbird feeders (expected back in Michigan next week, see when hummingbirds will get to you) and 2) plan a spring trip to a Great Lakes Basin island. Such trips are—or can be—for the birds! I suspect my island friends may be able to identify my bird, despite my poor description, because twice a year they have feathered visitors from other places migrating through, and many islanders tend to keep their eyes open for them.

Tree swallows staging for migration on Presque Isle, PA in mid-August.

We know that more than 140 species of birds depend on Michigan’s coastal habitat during their life cycle. And that millions of birds migrate through the Great Lakes every year, using wetlands, forests, shoreline and more than 32,000 islands as stopover sites. Even if you’re not a “birder,” if you enjoy watching local birds at your feeder or just enjoy being outdoors, that’s reason enough to launch yourself toward an island.

Try Springsong, May 6 – 8 on Pelee Island—join the 24-hour green “bird race” competing for the coveted Botham Cup—or the “Biggest Week in American Birding” Festival, May 6 – 15, on the islands of northwest Ohio: Kelleys, South Bass, Gibraltar, Middle Bass, Johnson’s, Catawba.

Or follow the birds north to other islands. Or west to islands. Or even east to islands. Check out the North American Migration Flyways.

Could my feathered visitor have been a warbler? Don’t warblers stay in the treetops? Do they even visit feeders, eat seed? My only species-specific bird book happens to be on warblers, but it’s on Pelee Island. And today, I’m stuck on the mainland.

If you’ve got the freedom to head for an island in the next three weeks, don’t forget a pair of binoculars when you check your island packing list. But forget birds for now; it’s time for . . .

Book Giveway Challenge #3

To win a copy of my book Great Lakes Island Escapes: Ferries and Bridges to Adventure, be first to identify where—in what province or state and between what two islands—the subject of the cover photo on my Facebook page can be found (see large photo above).

Will ponder your mystery bird over happy hour! Today brought scarlet tanagers, dozens of yellow rumped warblers and Palm warblers, a black throated green warbler, yellow warbler and bright blue jays…all to our yard and nearby bush! Such a delightful time of year!

Great blog, thanks for all the bird info, especially about hummingbirds!

We narrowed down the bird possibilities to white crowned sparrow or white throated sparrow. There are some colour variations…and of course the female options. That is our happy hour suggestion!

Thanks, Lynn! He or she looked larger than a house sparrow. The most distinctive features besides the rusty patches on each side of the crown were his/her very white breast with the black band at the neck. My books show yellow on the white-throated sparrow and there wasn’t any yellow. Maybe a “bleached” white-crowned sparrow. If you could reverse the white and gray on the white-crowned and add the neck band . . .

Here’s another guess at my mystery bird from Janet Scott, a friend of a blog follower: “House Sparrow males have gray caps, rusty brown on each side of cap and light breasts. When the chin patches are developing it could look like a stripe. Did your friend notice the beak, insect eater or seed eater?”

I’m sorry I didn’t notice the beak; the odd color combination was so striking. The bird was on my finch feeder and was definitely eating seed. But we have house sparrows galore and I’ve never seen one that looked like this.

Yesterday, I identified a male brown-headed cowbird at my feeder, not a particularly happy discovery.

Washington Island and Rock Island in Wisconsin

We have a winner! Congratulations, Karen Klein!