Have you ever had the experience that once you’ve begun noticing a particular something, suddenly, you see it everywhere? It’s hard to stop seeing it. Of course, we have a name for this. Several names, in fact, including: Baader-Meinhof phenomenon, frequency illusion, recency illusion, and selective attention bias.

What I Notice

Trees have been the subject of my selective attention bias for me as far back as I can remember. Other than people and dogs, trees are what I notice most in this inestimable world of ours. A noticing, which I recently learned even extends to the representation of trees in art. Or at least in Van Gogh’s paintings and drawings.

“Van Gogh in America”

If you had the opportunity to visit the Van Gogh in America exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), you may have noticed how very into trees Van Gogh was. You may also have noted that many of the trees in Van Gogh’s paintings are one of two species: olive trees or cypress trees. These were two of the species of trees he could see from his window and out on the grounds at the asylum Saint-Paul-de Mausole near Saint-Rémy de Provence the year he spent there (May of 1889 to May of 1890)[i]. In that one year, Van Gogh produced about 100 drawings and 150 paintings, 15 of those paintings had olive trees as their subject [ii].

Van Gogh’s Third Species of Trees

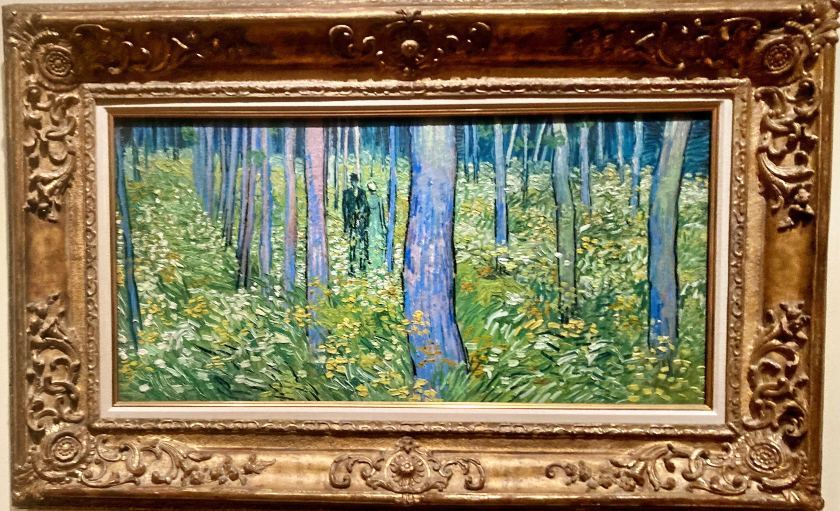

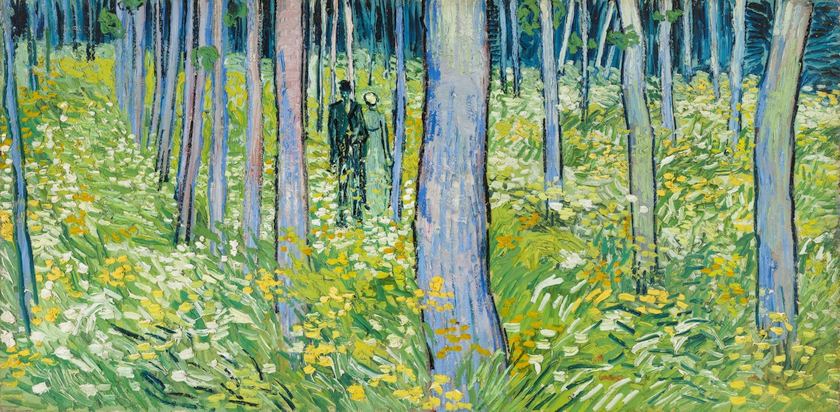

Several of the 74 pieces of his work in the DIA exhibit do have either olive trees or cypress trees as their primary subject. However, a third species is used to create both setting and characters—or, perhaps, more accurately, appears as a chorus—in Undergrowth with Two Figures (June 1890). Van Gogh described this painting, as well as providing a sketch of it, in a letter to his brother Theo, dated Wednesday, July 2, 1890 (25 days before he shot himself, 27 days before he died):

“. . . Then undergrowth, violet trunks of poplars which cross the landscape perpendicularly like columns. The depths of the undergrowth are blue, and under the big trunks the flowery meadow, white, pink, yellow, green, long russet grasses and flowers.”[iii]

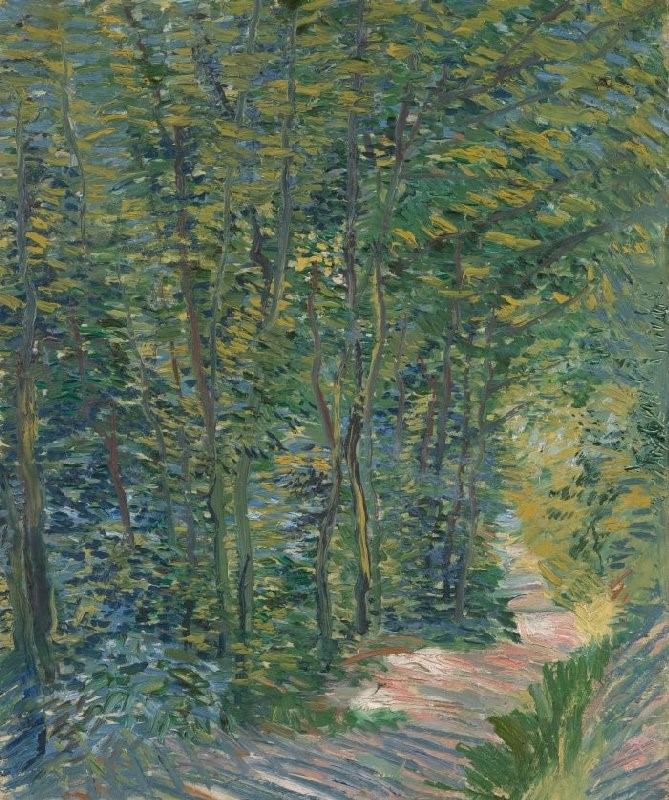

Van Gogh’s Other Poplar Paintings

Van Gogh had produced other paintings of poplar trees before this one, including:

- Poplar Trees (Nuenen, early 1884; pencil and ink study for Avenue of Poplars at Sunset below)

- Avenue of Poplars in Autumn (Nuenen, October 1884)

- Lane of Poplars at Sunset (Nuenen, October 1884)

- Symphony in Yellow[iv] (Nuenen, October 1984; today the painting is titled Poplars near Nuenen[v]and is believed to have been brightened up by Van Gogh in Paris in 1886.)

- Orchard in Bloom with Poplars (April 1889) (aka Spring in Arles and View of Arles, Flowering Orchards)

- Two Poplars in the Alpilles near Saint-Rémy (October 1889)

But what species of poplar trees was Van Gogh painting?

Lombardy Poplar?

The tall columnar poplars he features in many of his paintings look like the Lombardy poplars I knew in our early years of having a cottage on Pelee Island in Ontario. Planted along the west shore, age and the winds off Lake Erie eventually blew these Lombardy poplars down. I knew Lombardy poplars were native to Italy. But the tree trunks featured in Undergrowth with Two Figures don’t look like Lombardy poplars to me. We see only the tree’s trunks, no limbs; the trees in the painting don’t start branching until somewhere above the heads of the strolling couple. Unlike Van Gogh’s purplish poplars, the branches of a Lombardy poplar start close to the ground and grow upward, parallel to the trunk. Lombardy poplars wouldn’t create this “hypnotic mass of violet trees”[vi] above the undergrowth.

France was Europe’s first poplar producer, with poplar cultivation beginning there in the 1760s[vii], over 125 years before Van Gogh painted his poplars. I was curious about what kind of poplars are native to and had been cultivated in France, what Van Gogh might have been looking at when he was painting the poplars in this painting.

Black Poplar?

Aha! The native poplar species in France[viii] is the black poplar (Populus nigra), and Van Gogh’s trunks in the painting do look like those of the black poplar. In many online photographs, the black poplar’s dark furrowed bark has a faint pinkish-purple cast.

I was right about the origins of the Lombardy poplar (Populus nigra cv. ‘Italica’). This “other” poplar of Van Gogh’s was developed in Lombardy, a region in northern Italy. Turns out, the Lombardy is not a separate species; it is a cultivar of the black poplar. I was most interested in learning that all types of black poplar are a type of cottonwood poplar.

Have you ever known a cottonwood?

Eastern cottonwood[ix] (Populus deltoides) is the species of tree that I grew up closest to, both in proximity and in heart connection. When I first saw the cottonwoods growing along the creek in the field behind our suburban subdivision yard, I was a painfully shy first-grader, switching schools in the middle of the year.

The trees were huge and wild, belonging only to themselves.

They were also reliable beacons. Seeing the white parasols of their tiny seeds’ parachutes twirling against a deep June sky signaled the coming of summer vacation. The rustle of the cottonwoods’ dry leaves at the end of August triggered the excitement of a new school year approaching.

Until I turned 14 and my family moved, these poplars were my setting, were the dominant characters in my personal landscape. They appeared bigger and older than anything else in my world. And more steadfast. I have always had the distinct feeling they were benevolent beings watching over me.

Tree Tales

Perhaps one might expect that eventually, being a writer, I would write about trees, given that trees are one of the primary things I notice in the world. Always and wherever I am. And trees, when looked at and considered carefully, never fail to evoke awe in me. (And, we are only just beginning to understand how important awe is to our well-being.)

But I am a little surprised about the tree stories that came to me unbidden. In February of this year, before the first tree flowers to bloom in Michigan—the flowers of the silver maple—open, my new book, Divining, A Memoir in Trees will be released. The first essay I wrote for this book is about the Eastern cottonwood, just one species in the Willow family (Salicaceae), which contains some 35 species, including the black poplars—that wonderful chorus lined up in rows, their trunks dwarfing the humans in Van Gogh’s painting. The ninth essay in the book, “Pages from a Cottonwood Calendar,” is the story of my falling in love with trees and with writing.

Will you come too?

Once Divining, A Memoir in Trees is released next month[x], at this website, you’ll find additional information about each of the 16 tree species with whom I’ve shared parts of my life and who are each a subject for one of the essays in the book.

And you’ll find me, still wondering about and wandering among trees.

I do hope you’ll take a weekly walk with me to explore what it is about trees that fascinates.

[i]Born in Zundert, Netherlands on March 30,1853, Vincent van Gogh moved to France in February of 1886, where he spent two years in Paris before moving south to Arles, then being institutionalized in Saint-Rémy de Provence, and finally settled briefly in Auvers-sur-Oise, outside of Paris, where he died on July 29,1890 of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

[ii] “When [V]an Gogh Spoke for the Trees by Amy Crawford, Smithsonian Magazine June 2022 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/van-gogh-trees-exhibition-180980048/.

[iii] Letter 896 to Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger, Auvers-sur Oise, Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, Nienke Bakker (eds.) (2009), Vincent van Gogh – The Letters. Version: 1. https://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let896/letter.html#translation

[iv] “Poplars near Nuenen,” Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

[v] “Poplars near Nuenen” has been dated, based on a letter Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, as having been painted in October 1884, but it is thought that the painting was reworked two years later in Paris with brighter colors.

[vi] Van Gogh in America guide to the exhibit, p. 7 (Detroit Institute of Arts, 2022). While the rows of violet tree trunks may be “hypnotic” in their rows, it is the undergrowth of grasses and flowers that creates a “mass.”

[vii], “Poplar Is a Fundamental Resource for France’s Rural Life,” ProPopulus, October 30, 2020, https://propopulus.eu/en/poplar-is-a-fundamental-resource-for-frances-rural-life/

[viii] Black poplars are native to the rest of Europe, southwest and central Asia, and northwest Africa as well.

[ix] The Eastern cottonwood is native to North America, growing throughout the eastern, central, and southwestern United States, the southernmost part of eastern Canada, and northeastern Mexico. Black cottonwood (Populus balsamifera)—different from black poplar (Populus nigra)—found west of the Rocky Mountains, from northern Baja California to Kodiak Island, Alaska, and Fremont cottonwood (Populus fremontii) found in California, east to Utah and Arizona and down into northwest Mexico.

[x] Divining, A Memoir in Trees will be released by Wayne State University Press on February 21, 2023.