The other day, my daughter Meagan texted me a screenshot of a posting from her Facebook parent group. It was of a 4.3-starred destination to visit. The name of the destination was “Tree That Owns Itself.” Have you ever heard of this? I hadn’t.

The tree is a white oak (Quercus alba) at the corner of South Finley and Dearing Streets at the edge of downtown Athens, Georgia. This tree is protected from removal by humans in a very unique way. Legend and some histories state that the tree was deeded legal ownership of itself and the property rights for the radius of eight feet of land surrounding the base of its trunk. William H. Jackson is identified as the man responsible for conferring the deed to the white oak.

The Tree’s Deed

Multiple places online, including at Atlas Obscura you can find a portion of the purported words of the deed reproduced on the marble marker. You can see this marker to the right of the tree’s trunk in the photo above. The words on the marker read:

“For and in consideration of the great love I bear this tree and the great desire I have for its protection for all time, I convey entire possession of itself and all land within eight feet of the tree on all sides. William H. Jackson”

—Engraved on the marble marker at the foot of the Tree That Owns Itself

The other structures visible in the photo are eight granite posts holding the chain that surrounds the tree’s trunk.

We know who erected the marker and granite posts and when they were added. In 1906, several years after Jackson had died, Philanthropist George F. Peabody–after which the George Foster Peabody Awards program was name and which honors what are described as “the most powerful, enlightening, and invigorating stories in television, radio, and online media,”–added the marker, the posts and chain, and even some rich topsoil around the tree’s roots.

Was this attention to the tree Peabody’s attempt to keep a powerful story alive?

Because no one alive today can find the deed. No one alive in 1966 had seen the deed.

First Documentation

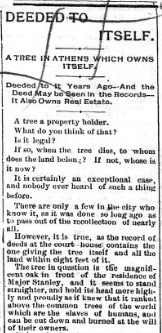

The only person we know who should have seen the deed is a newspaper reporter. The first mention of this deed–according to whatever source one consults–appears to be on the front page of the Athens Weekly Banner on Tuesday, August 12, 1890.

However, the story has no byline.

Even the Wikipedia entry for “Tree that Owns Itself” is divided into two sections: “Legend” and “History.” Both sections contain some “citation needed” tags.

What We Do Know

- According to the Farmers’ Almanac, the original tree that was deeded ownership of itself “sprouted between the mid-1500s and late 1700s, long before the area turned into a residential neighborhood. When Athens was formed, it was considered to be the largest tree in the town — over 100 feet tall.”

- William H. Jackson was born in Savannah in 1786, the son of James Jackson. James Jackson has gone down in history as a great patriot of the American Revolution who served as the governor of Georgia after the Revolution.

- William H. Jackson lived on or near the property, which originally belonged to the University of Georgia, on which the tree in question was growing although he may never have actually owned the land, and he left Athens in 1832. (Jackson and his brother were students in the first graduating class of the University of Georgia in 1804, which is how he initially came to Athens.)

- The deed supposedly was recorded between 1820 and 1832.

- No property deed has been found in the deed records of Athen’s Clarke County that addresses any tree’s ownership of itself at any time.

- The people of Athens have never contested the tree’s rights to the land.

- The Tree That Owns Itself has been an historical landmark and tourist attraction for over a century. A postcard produced in 1920 with the caption “The Only Tree in the World That Owns Itself, Athens, Ga.,” can be seen here. The tree is even a notable spot on the mobile phone game, Pokémon Go, which generated additional street traffic during the game’s heyday.

- And traffic is an issue. The land “owned” by the tree protrudes, shrinking a portion of South Finley Street into a one-lane road, even though it still is open to two-way traffic.

The Heir

White oaks, under perfect conditions, can live to be 300 or more years old. The original white oak–with official estimates of being 150 to 350 to 400 years old at the time–blew over in a windstorm on October 9, 1942.

In 1946, the newly formed Athens Junior Ladies Garden Club, searching for a first project, transplanted a replacement for the tree that owns itself. This transplant had, purportedly, been started from an acorn from the original tree. On December 4, 1996, the current Junior Ladies Garden Club threw a golden anniversary party for the Son of the Tree That Owns Itself.

By 2020, the current Tree That Owns Itself had acquired the stately height of 50 feet.

A Thorough Investigation

If you want to read an account that attempts to separate the history from the legend, the best I could find was in Chapter 2 (which you can scroll to from the link, which follows) of the book The Toombs Oak, the Tree That Owned Itself, and Other Chapters of Georgia by E. Merton Coulter (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1966), titled “The Story of the Tree That Owned Itself.”

I invite you to go down the same rabbit hole I enjoyed in reading about this tree by following all the links above (and then some).

Should Trees Have Legal Standing?

But what this story–folklore or fact–reminded me of was an article I read in 2014. At the time, I was casting a wide net for anything that would help the Vinsetta Heights Property Owners Association (VHPOA), our Royal Oak neighborhood group, prevent the community of beech trees in my neighborhood from being cut down in order for four houses to be built where two homes stood on large wooded lots.

At least that was my objective. VHPOA’s stated objective was to make the city allow only two or, at the most three, houses where there had been only two houses since the middle of the last century. Instead of the eight that the developer was planning. (The fourth house–of four–is currently under construction.)

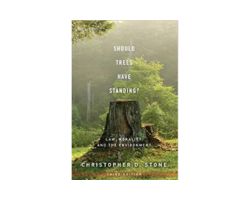

While looking for resources to bolster our position, I came across the article “Should Trees Have Standing?–Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects?” This article by law professor Christopher D. Stone was published in the Southern California Law Review in 1972.

“I am quite seriously proposing that we give legal rights to forests, oceans, rivers and other so-called ‘natural objects’ in the environment — indeed, to the natural environment as a whole.”

–USC Gould Law School Professor Christopher D. Stone

U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas cited Stone’s research in a dissent against a 4-3 SCOTUS decision in 1972 that the Sierra Club had no standing to sue the Walt Disney Company, then planning to build a resort on public land in the Sierra Nevada.

The Book

Thirty-five years later, a book based on the impact the article had on environmental law and ethics, Should Trees Have Standing? Law, Morality, and the Environment (Oxford University Press, 2010), by Stone, was published.

In the introduction to the book, Stone explains how the idea of natural objects in the environment having legal standing came to him.

“My thoughts were not even on the environment. I was teaching an introductory class in property law . . . we were approaching the end of the [class] hour. I sensed that the students had already started to pack away their enthusiasm for the next venue. . . . They needed to be lassoed back,” he writes.

“‘So,’ I wondered aloud . . . ‘what would a radically different law-driven consciousness look like? . . . One in which Nature had rights,’ I supplied my own answer. ‘Yes, rivers, lake, . . . ‘ (warming to the idea) ‘trees . . . animals . . .’ (I may have ventured ‘rocks’ I am not certain.) ‘How would such a posture in law affect a community’s view of itself?'”

Christopher D. Stone in his Introduction”Trees at Thirty-Five” to his Should Trees Have Standing? Law, Morality, and the Environment

Stone goes on to explain the outcome of his statement intended to lasso his students’ attention. It worked:

“This little thought experiment was greeted, quite sincerely, with uproar. At the end of the hour, none too soon, I stepped out into the hall and asked myself, ‘What did you just say in there? How could a tree have ‘rights?’ I had no idea.

“The wish to answer my question was the starting point of Should Trees Have Standing? It launched as a vague, if heartfelt, conclusion tossed off in the heat of lecture. My intial motive was to restore my credibility [emphasis added]. I set out to demonstrate that, whatever other criticisms might be leveled at the idea of Nature having legal rights, it was not incoherent. . . .”

Christopher D. Stone in his Introduction”Trees at Thirty-Five” to his Should Trees Have Standing? Law, Morality, and the Environment

One never knows where an idea that comes up in the “heat of the moment” and for an entirely different reason might go. When Christopher Stone died two years ago, the New York Times ran his obituary under the headline: “Christopher Stone, Who Proposed Legal Rights for Trees, Dies at 83.”

Another White Oak

After having spent some time yesterday putting together some ideas about “the tree that owns itself,” I took a break to walk around the block. A gray evening it was. I was thinking about this posting when I was shocked out of my musings. Something was very obviously missing from a park lawn (the area between the sidewalk and street curb) on a house behind and kitty corner from mine.

What Was Missing?

An oak that was nearer and dearer to me that the Tree That Owns Itself. An oak that was as healthy as healthy could be.

Clearly, this is an oak that did not own itself.

How Would You Answer This Question?

What tree do you know to which you would like to deed ownership of itself? Give it some thought.

I have two or three trees with whom I share land to which I’m particularly drawn. If I had to pick one, it would, for sure, become a “Sophie’s choice.”

- Would it be the American beech on the property line shared with my neighbor Kate, the easternmost beech in what was once a grove on the banks of the (now underground) Red Run?

- Or the American sycamore, my arboreal ally, the one who I was gifted baby photos of by the city assessor?

- Or the ginkgo that was a Mother’s Day present to the woman who loved this house and land before me?

To what tree do you wish you could deed the ownership of itself?

The Bebb Oak on Livernois Rd. in Rochester Hills gets my vote for being a tree truly deserving to “Belong to Itself.” You can Google it for photos–or better, drive there with a load of kids. It’s amazing to see how many it takes to encircle the trunk and the branches can hold a whole classful of children without dipping down. I drove by this tree every morning on my way to teach school nearby. I’ve long wanted to remove the ugly signs around the tree. And if I could, I’d move the road over as well. I bet the tree was there first!

I know that tree, Maureen, and I agree. I thought it was a burr oak. I just looked up “Bebb oak.” Bebb’s Hybrid Oak is a naturally occuring cross between a White Oak and a Burr Oak. I’ll bet you knew that. The hybrid was named for Michael Schuck Bebb (1833–1895), an Illinois botanist who specialized in willows. According to Morse Nursery, “This hybrid becomes a very large tree and starts producing the sweet acorns at a young age.” Here’s a link to an article about that particular Bebb oak on an Arbor Day 12 years ago: https://patch.com/michigan/rochester/whats-more-lovely-than-the-bebb-oak-tree This Friday is Arbor Day. Do you have any tree plans?