If there were such a thing as a “Field Guide to Happy Grandchildren,” I’m guessing being present for their birthdays would be one of the characteristics listed.

When my oldest grandson, Caden Daly, turned five at the end of May, both sets of grandparents–Nick (aka “Grandpa Nick”) and Rhonda (“Ra-Ra”) and my husband (“Bumpy”) and me (“MoMo”)–joined Caden Daly’s parents, my older daughter and her husband, in Durham to celebrate.

A Surprise Gift for Me

The Carolina Friends School’s beautiful birthday celebration–“Surrounded by Love” began his day. And he was certainly surrounded by love from his classmates, teachers, and parents. And by grandparent love times four!

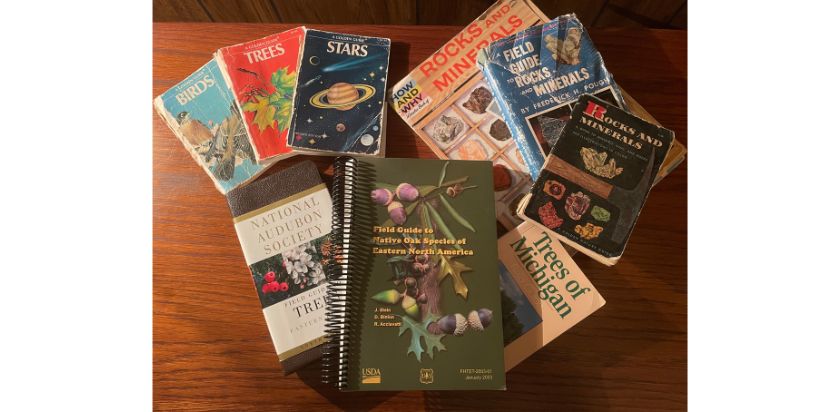

At this event, I received an unexpected gift. Caden’s Grandpa Nick–knowing my penchant for trees–gifted me the Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America by John Stein, Denise Binion, and Robert Acciavatti (Morgantown, WV: USDA Forest Service, 2003).

Like the book’s title states, this a field guide of just oaks, and more specifically of just native oak species from just the eastern part of our continent. It’s full of photos, sketches of leaves and acorns, and distribution maps. The text includes details on each tree’s growth form, bark, twigs and buds, leaves, acorns, habitat, distribution, and “commentary,” the last section of which contains miscellaneous interesting facts about the species.

The Origin of Field Guides?

Nick’s field guide is the most specific field guide I’ve ever seen. It started me thinking about field guides in general. After scientists had done the naming work, how did it happen that ordinary humans got interested in identifying the nonhuman pieces of our world by creating and consulting field guides?

I wondered to what species identifications the first field guides were guiding their readers. Who wrote them and when? I turn to our crowd-sourced field guide to human knowledge:

Popular interests in identifying things in nature probably were strongest in bird and plant guides. Perhaps the first popular field guide to plants in the United States was the 1893 How to Know the Wildflowers by “Mrs. William Starr Dana” (Frances Theodora Parsons). In 1890, Florence Merriam published Birds Through an Opera-Glass, describing 70 common species. Focused on living birds observed in the field, the book is considered the first in the tradition of modern, illustrated bird guides.

— https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Field_guide

Not Wildflowers or Birds

My history with field guides, however, did not begin with wildflowers or birds.

It began with rocks.

My Aunt Muriel, my dad’s half-sister, who lived in Winston-Salem, NC, was a gemologist. She and my Uncle Ronald Rice, a Baptist pastor who worked for social justice, visited my paternal grandparents in Detroit’s Brightmoor neighborhood every other year. The first visit I recall was when I was in first grade. We sat at my grandparents’ dining room table after Grandpa had cleared away the dinner plates and looked at the rocks and minerals she had collected, the gems she had mined, the jewelry she had made from cabochons she had cut, and the “stones” she had faceted.

Aunt Muriel called anything from a faceted blue topaz to a pebble I’d picked up on the gravel path in The Field a “stone.”

Reading for a Rockhound

And after that visit, I did start spending time squatting alongside the gravel path that traversed the field behind our house from a pedestrian bridge across the Bell Branch of the Upper Rouge River to the dead-end side street adjacent to our house. I was looking for unusual stones. I quickly developed a thing for pink feldspar. Do you know feldspar? I still do look for its special sheen and intersecting cleavage planes. My granddaughter, Avery Grace, about to enter second grade, with her Dad’s help, has collected some nice feldspar specimens over the years for me.

In second grade, I was saving my allowance for a copy of The How and Why Wonder Book of Rocks and Minerals by Nelson William Hyler (Wonder Books, 1960–the 25th edition). Once I had enough to purchase the book from the Montgomery Ward department store at Wonderland Center in Livonia, I kept it at the ready in my bedroom to help me identify the stones that caught my eye. (I was not deterred by the fact that the cover showed a boy at a microscope; I received my own microscope in fourth grade, a Christmas present from my maternal grandparents.)

That beginner’s field guide was eventually joined by another: A Golden Nature Guide: Rocks and Minerals by Herbert S. Zim (New York: Golden Press, 1962–the 16th printing). As well as a more advanced one: A Field Guide to Rocks and Minerals by Frederick Pough (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960), the #1 item on my Christmas list the year I turned 11. That book is inscribed: “Christmas 1964, Maureen Dunphy, With love from Mother and Daddy.”

Field-Guide Collection Expansion

I was a big tent-camper before meeting my husband. Our first trip was a camping trip to the Rocky Mountain National Park, ten weeks after we met, five weeks after we first went out together. The trip had been planned by a small group of other people who neither of us knew well . . . and who never materialized. The rest is history, our history. For our second year of camping together, on his birthday, I gave Craig a small set of Golden Guides, which I’d assembled on three subjects and inscribed, referencing our relationship:

- Trees — “You’ve got me climbing trees over you.”

- Birds — “May the bluebird of happiness be yours.”

- Stars — “Under the stars . . . “

Later, when our daughters joined us camping, we added more Golden Guides to our set: Butterflies and Moths; Flowers; Fossils; Geology; Insects; Pond Life. All of these field guides eventually resided at our Pelee Island cottage and were often consulted in identifying what we were seeing out in nature on the island.

What I Turn to Now

Today, the pocket field guides I rely on most for everyday use are Stan Tekiela‘s Trees of Michigan and Birds of Michigan. His Birds of Prey of the Midwest Field Guide has come in handy in identifying to what species of hawk the chipmunk-hunters from the tree canopy outside my study window belong.

When I was working on my tree book, I particularly appreciated the National Audubon Field Guide to Trees: Eastern Region. I already had a well-thumbed National Audubon Field Guide to Birds: Eastern Region.

The National Audubon Society, through Penguin Random House, publishes a total of 29 field guides, including guides to wildflowers, butterflies, mushrooms, fossils, rocks and minerals, insects and spiders, reptiles and amphibians, mammals, marine mammals, fishes, seashore creatures, shells, weather, and the night sky. And regional field guides of the United States, which appear to cover all of the regions of the country–with California and Florida having their own guides–except for the Midwest. What’s up with that?

A Question for You

Do you have a field guide (or two) lurking on your bookshelves or stashed in your car’s glovebox for quick ID-ing? What is it guiding you in identifying?

Please consider sharing your answer to the question above in a Comment to this blog posting.

(This would also help me see if the Comments function is working again; my website has recently been moved to a new web hosting service provider.)

Looking Ahead

Next week’s posting on this blog will be by a guest blogger: Sondra Willobee. Sondra is an author, a fine writer, and a writing friend of mine. She posts regularly on her blog Down by the Riverside. Here’s a pertinent blog post of hers to check out from 2021: “Eve in the Garden” which references her use of a nature guide. The post “Touching the White Oak,” which she so graciously wrote this blog, will be showcased here next week.

Meanwhile, if you’re interested, you can read up on the white oak tree species in More Tree Information: White Oak on my website or in “Nick’s field guide,” pages 8 – 9. Thank you, Nick Somarelli, for the Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America! And for the opportunity it provided to explore the role field guides have played in my life.